The cost of producing milk in New Zealand continues to compare favourably with other dairy-exporting regions despite a structural lift in global milk production costs across the past five years, according to a new report by food and agri banking specialist Rabobank.

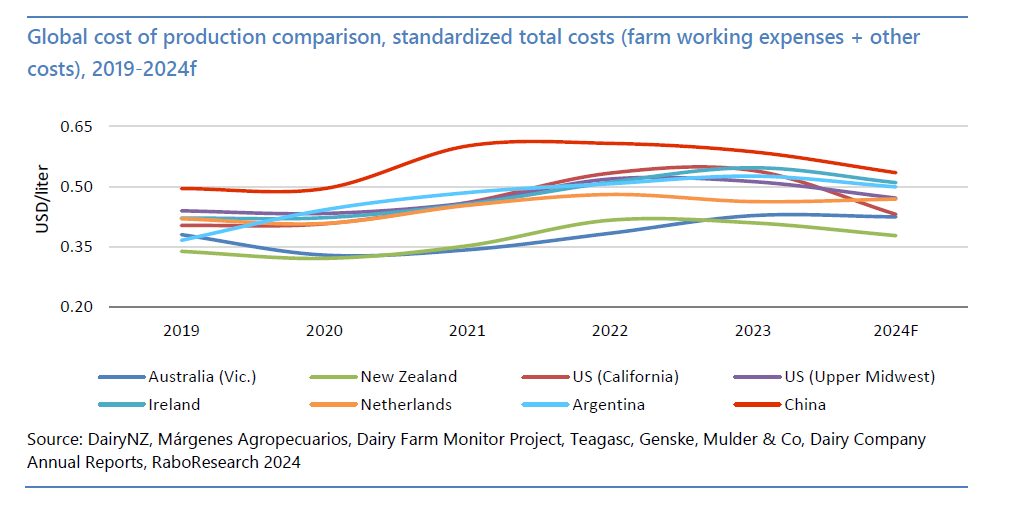

In the report, The cost of milk: dissecting milk production costs, Rabobank says dairy farmers in many dairy-exporting regions have felt the pressure of increasingly higher milk production costs over recent years with the average total cost for milk production across eight major exporting regions (Argentina, Australia, China, Ireland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, California and the Upper Midwest of the US) increasing by around US6c/litre from 2019 to 2024 (up by 14%) with over 70% of the increase occurring since 2021.

Report author Emma Higgins said production cost increases have been broad based.

“The majority of the cost pressure has been on ‘Farm Working Expenses’ rather than other ancillary costs such as servicing debt, taxes, and depreciation,” she said.

Emma Higgins, Senior Agriculture Analyst, RaboResearch

“The latest dramatic cyclical cost jump, beginning in 2021, has occurred amongst a unique backdrop, differing from other price hike cycles. Feed and fertiliser cost increases at the farmgate resulted from inclement weather, the fallout of the Ukraine war increasing energy prices, trade disruptions, elevated shipping cost and broader supply chain disruptions.

“This coincided with monetary policy cycles shifting in response to Covid-induced inflation. Interest rates lifted rapidly, increasing the cost of servicing new and existing debt, alongside the resulting general overhead cost inflation. At the same time, labour costs moved structurally higher in response to either a combination of policy settings or staffing shortages in most producing regions.”

The report says costs lifted across the eight regions in 2021-2022, and remained elevated through 2023, until 2024 when all areas experienced relief, narrowing the cost band back to 2019 levels.

“Feed expenses have been the largest culprit in cost increases, with average feed bills across the eight regions rising 19% from 2019 to 2024,” Ms Higgins said.

“Feed receipts started to pull back due to yield improvement and good weather in 2024, while fertiliser costs have also retreated as supply remains ample for demand. Interest rates are declining in many regions as the easing cycle for monetary policy begins.”

Ms Higgins said key cost categories varied by region.

“The proportion of feed costs as a percentage of overall costs is generally lower for extensive and quasi pasture-based feeding systems like New Zealand, the Netherlands and Ireland,” she said.

“In contrast, feed bills for more intensive farming systems like those in China and the US, tend to make up a higher proportion of overall costs with this largely down to greater volumes of imported feed.”

Of the eight regions assessed, the report says, labour cost increases have been the most significant in Australia across the past five years – jumping by over 50% in local currency since 2021 – while interest rate pressures have been felt the most by New Zealand, Australian and Argentinian producers.

Global milk production costs comparison: Oceania leads the way

The report says New Zealand and Australia have competed neck and neck with each other over the past six years to hold the title of lowest-cost producer in US dollar terms among the eight assessed regions.

“New Zealand is currently in the lead, having increased its cost advantage to USc5/litre in 2024 (up from USc2/litre in 2023) as Australia has grappled with higher labour costs,” Ms Higgins said.

“The five-year average total cost of production sits at US 0.37c/litre for both New Zealand and Australia, compared to around US0.48c/litre for the other regions. The Oceania region’s strong reliance on pasture-grassing, supplemented with home-grown feed stuffs or locally produced-feeds has more broadly supported its low-cost of production positioning.

“With this comparison being made in USD (US dollars), NZ and Australian production costs have also benefitted from a 9% and 8% discount, respectively, in 2024 compared to 2019, based on a stronger USD compared to their local currencies.

“The downside of a stronger USD for non-US production regions is the impact on cost pressure for imported inputs. Fertiliser and fuel cost items tend to feel this pressure most keenly in Oceania, averaging around 15% of New Zealand farm working expenses in the last 5 years.”

Ms Higgins said China remains the highest cost milk producer – but it has become more cost-competitive in the past three years.

“Feed costs make-up over 60% of China’s total costs of production, with farming systems relying on large quantities of imported feed (and other inputs). Weaker feed prices in 2023 and 2024 have helped to improve China’s costs, supported by double-digit percentage declines in corn and soybeans prices in 2024,” she said.

Since 2019, the report says, the regions generating the best cash flow on a gross milk price margin calculation basis (i.e. milk price minus operating costs) have been NZ, Australia and Netherlands.

“These regions have experienced constant positive milk gross margins through the cycles and lower volatility compared to other regions,” Ms Higgins said.

Production costs out to 2035

Ms Higgins said the dairy sector has experienced significant price and costs volatility during the past decade.

“And it is fair to say that will not change in the future, as the geopolitical environment becomes more unstable, giving rise to the risk of higher inflationary settings, weaker economic growth, climate variability and a potential decline in international trade,” she said.

“Continued cost structure management, relative to milk output, will be required to maintain dairy farmers’ economic resilience in a potentially turbulent business operating environment – something Kiwi dairy farmers have demonstrated in previous commodity price down cycles.”

Ms Higgins says RaboResearch anticipates a variety of implications for dairy value chains will likely exist in the years ahead.

“These include a volatile operating environment and increased regulatory pressures which will raise the complexity of dairy farming businesses, consolidation and rationalisation of dairy industries in certain regions, and a need for dairy producers to optimise dairy cow nutrition and increase focus on focus on genetics and consideration of input use,” she said.

“Ultimately, dairy producers will need to maintain strong milk margins to fund such productivity improvements within an increasingly complex business environment. As such, dairy exporters and traders will require a stronger understanding of supply dynamics and profitability drivers for dairy farmers.”

The report says China is expected to remain a dairy importer over the medium term.

“However, as China becomes more cost-competitive in its own domestic production, with a growing milk supply base, the ramifications continue for exporters who have historically relied upon a strong Chinese demand and a higher Chinese base price to support import price arbitrage, which further increases the risk of price volatility for dairy farmers supplying such exporters,” it said.

RaboResearch Disclaimer: Please refer to our disclaimer here for information about the scope and limitations of the RaboResearch material provided in this media release.